News

Marketer Magazine: On The Record: Conducting Strong Interviews with the Media

Who’s Minding the Storage? A Brief History of How We Saved Our Lives

"The whole meaning of life? Trying to find a place for your stuff. Your house is just a place for your stuff, while you go out and get more stuff!

And maybe put some of your stuff in storage.

There’s a whole industry based on keeping an eye on your stuff."

— George Carlin

Long before primitive man was aware of the concepts of preservation and communication, his desire to do both was inherently there.

Scribbling on cave walls, he seemed compelled to record what he saw and experienced. Struggling to get a handle on his thoughts and emotions. To understand. And, to be understood.

While we may never know for sure what was in his mind, we do know it was in his blood.

Archiving is the collecting, organizing, preserving and controlling of records and documents. Fortunately for us and our history, this process, this compulsion is a balance of head and heart, intellect and sentimentality. Which assures us that no matter what it is, someone is passionate enough to be there, save it and pass it on.

The earliest examples of cave drawings or “picture writing” are more than 40,000 years old. But as tribes emerged from their caves, the complexity of their symbols and images grew, as did their ability to store more information. And tell a better story.

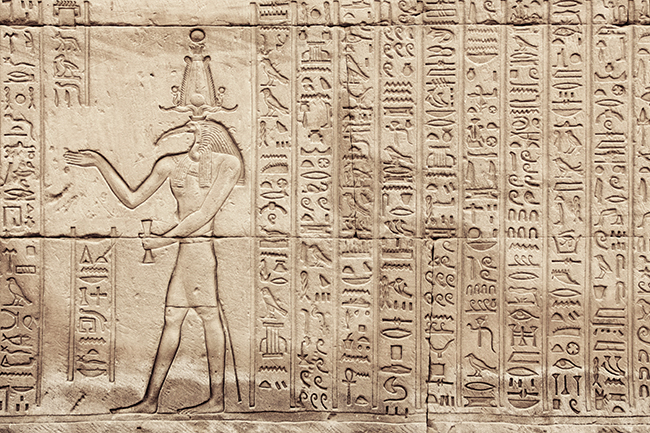

More than 2,000 years before letters and alphabets were all the rage, Egyptian hieroglyphics were considered the height of scrapbooking sophistication. With as many as 1,000 distinct characters, these sacred words were written on parchment from the papyrus plant or carved on the walls of tombs and temples, chronicling pertinent information and more importantly — creating crucial timelines of our world’s history.

But the fragile papyrus was defenseless against the elements and carvings proved to be inefficient, forcing archivists to adopt storage methods nearly as voluminous as the information itself.

More weather-friendly parchments were made from animal hides. Notches were carved in sticks, bones or broken shards of pottery. Indentions were pushed into wax and images were chiseled into clay or stone. Numbers were even recorded by knotted strands of animal hair or multi-colored cords of cotton.

Anything and everything on hand was enlisted to help keep records of their lives.

Sure, each method was a slight improvement on the one before, but even the best innovation of the day lacked in durability and flexibility. Which meant that centuries worth of significant events were destined to be lost, disintegrating into dust.

Consider the unfortunate fate of archives from philosophers like Aristotle. While he penned more than 200 books that pushed the boundaries of man’s intellect, only a few dozen survived. And those that did were written and rewritten from one language to another so many times it makes one wonder if the true authenticity of his thoughts and observations were literally lost in translation.

One man’s trash is another man’s tax return

What to save? What to sack? These top tips for archiving documents can help you figure out the stuff in your life that continues to move you or needs to be moved to trash. Because it may be time (as Elsa reminded us) to Let it Go.

Ok, that’s the bad news. The good news? Each new civilization shared the same frantic obsession to save as the one before. And so, for the next millennium (give or take) hand-written accounts using pens made of cane, bird quill, reed or metal and inscribed on more reliable animal-skin parchment became the mainstay of recording historical information.

Because the content of what was recorded was determined by a select few, and carried out by fewer still, the clear majority of subject matter centered on religious teachings and scripture.

We’ve all heard tales of monks who labored up to 14 hours a day for four years to complete a single Bible. And when combined with the fact that most of the world was illiterate, access to history was coveted and rare.

That is until Johannes Gutenberg showed up. A German blacksmith and inventor, his introduction of a printing press with movable type began a global revolution like no other, giving overworked monks a much-needed breather. The ability to print books brought enlightenment to the masses, increased literacy at alarming rates and allowed news to spread as fast as the fleetest ships. It advanced not only religious teachings but science, philosophy and poetry. It reintroduced the lost works of great thinkers. It created platforms for anyone with something to say. And it made Martin Luther the first best-selling author.

In 2000, the History Channel ranked the 100 most influential people of the past millennium. Coming in at #1 was Johannes. So yeah, his contribution was kind of a big deal.

For the next 400 years, the collection and preservation of our world became faster, easier and more importantly, enduring.

The next revolution in historical storage occurred in 1826 when Joseph Nicéphore Niépce tested a new technique he called heliography and took the first photograph. The impact of the visual component to our society, culture and heritage was immense because it not only added validity to text and immortality to historical events, it gave new meaning to the phrase “a picture is worth a thousand words.”

One characteristic of our obsessive need to chronicle is that we take great comfort knowing it’s there, safely stored away and ready at a moment’s notice should we want to look at it.

As it turns out, we did.

To satisfy humanity’s insatiable desire (and unending curiosity) to know, people in charge began to organize the massive volumes of printed books and photography, paintings and sculptures, pottery and tools, clothing and whatever else they had in store. And what followed was an explosion of libraries, museums and exhibits of every kind. Whether entertaining or educational, each was designed to provide a never-seen, up close and personal glimpse of cultures, customs and momentous stories from once upon a time.

Thus far, we’ve learned that since primitive times, we’ve been impelled to express, and experimented with equally primitive ways in which to hold that expression.

But hold onto your hat. Because from the mid-19th century on things get really interesting.

In the 1850s, in search of the ideal storage method to complement the breakthrough technology of photography, Edouard-Leon Scott gave us the phonautograph, the first device that could record sound.

Twenty years later, Thomas Edison combined the phonautograph, telegraph and telephone to create the phonograph. It had one needle to record the sound and a second needle to play it back. The first recording of the human voice was Edison himself reciting Mary Had a Little Lamb.

As methods that aided in the archiving of all things, these were breakthroughs of unheard of proportions.

But only a short 15 years later our man Edison, along with assistant William Dickson, really set data storage into motion with the Kinetoscope, the first motion picture camera that (as promised by Edison himself) did for the eye what the phonograph did for the ear.

For archiving and for all of civilization, history had come alive. And another dynamic dimension to the storing and observance of information had been added.

As the 20th century unfolded, so did the variations and improvements in these new technologies. In photography, clarity and capability progressed with flying colors. In acoustics, the enhancements from 78 to 33, from cassette to 8-Track and from CD to Spotify was enough to make any archivist’s head spin. And motion pictures? They have combined the best of all these worlds, offering living accounts of history as limitless as they are moving.

But no era has done more to advance archiving than the digital age.

Now perhaps modern-day folk are a bit jaded, and not as impressed with the shiny objects around us. Archivists would tell us we should be. From the web, smart phones and all the grandware within them, the internet has not only brought the world to our fingertips but given us ample storage and immediate access.

And the difference in capacity and capability before and after the digital age is the difference between a sand pail and the Grand Canyon.

Beyond its incomprehensible amount of storage, digital archiving is also easy to locate and manage. Saves you money. Takes precautions to keep you and your stuff safe, protecting your business and your business. While adding genuine value to your brand, message and mission.

Corporations such as Amazon or Walmart deal in billions of bits of information that are organized, categorized — and utilized to their full advantage. Creating instantaneous dossiers on consumers that determine who you are, where you are and what you want. And with every click, they can archive just a little more.

But just how big are these billions of bits?

Your average iCloud provides 2 terabytes of storage space, with room for roughly 2,000,000 photos and a lifetime of selfies.

And in only one hour, Walmart collects 2.5 petabytes of data from a million people (in old school measurement, that equates to about 20,000,000 filing cabinets) and have on file filtered, detailed records on 145 million customers — or 60% of the adults in the U.S.

That’s how big.

The hunger to capture and save our experiences is encoded. And with each new day, as our hunger and experiences grow we’ve made sure we’ll always have room for more.