News

Marketer Magazine: On The Record: Conducting Strong Interviews with the Media

Classical Music: The Unseen Parts

Like notes of music in a barline are a code of sorts, so too is the tactile coding system of Braille. The surface-level similarity between the two systems is relatively apparent: organized dots that create meaning when understood. While a bar of music is seen by the musician, Braille is touched by the reader. And when either system is used with skill and passion, they can be felt by the bystander.

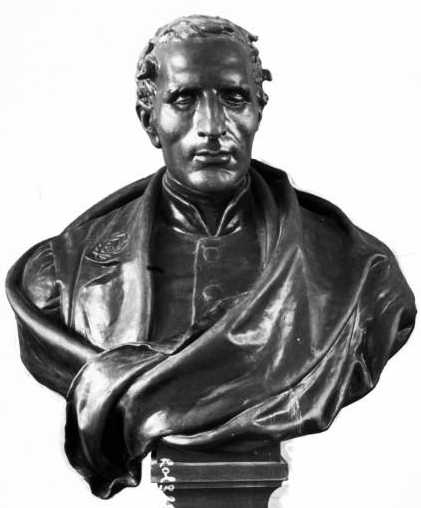

The convergence of Braille and music dates back to the 1800s in France. It was 1824 when Louis Braille introduced his homemade coding system to his peers at a school for the blind, but whether he realized it or not, Braille’s conceptualization of his now world-renowned system began when he was just three years old.

As a young child, Braille liked to spend time in his father’s workshop. He made harnesses out of leather and there were always sharp tools strewn about. Braille was playing with a stitching awl, trying to puncture a piece of leather, when he got a little too close and his hand slipped. The awl punctured his eye and he lost vision in one eye. Unfortunately, an infection spread that rendered his other eye useless, too. Young Braille was sent to a school for blind children, and that’s where he began devising his coding system.

Music was an important aspect of Braille’s life and a therapeutic one. When he created his system, he was sure to incorporate a way for people with impaired vision to read music.

His addition of music to his Braille system wasn’t just self-serving. Many classical musicians who gained great fame in the 20th Century were visually impaired. Take the German Bach scholar Helmut Walcha for example. He’s touted as one of the greatest organists of all time. The list goes on: Louis Vierne (1870–1937), Andre Marchal (1894–1980), Gaston Litaize (1909–1991) and Jean Langlais (1907–1991).

We’re only scratching the surface. Today, musicians with impaired vision are using the coding system to create masterpieces so compelling that we’re left certain their composers have an extra sense instead of lack one.

Interestingly, blindness isn’t the only impairment that’s prevalent in the world’s cohort of skilled classical musicians. Ludwig van Beethoven was deaf. The idea that Beethoven never heard his music in the same way we have could be considered a tragedy – but a beautiful one. Much like a child losing his vision in an accident and going on to change the way the world sees.