News

Marketer Magazine: On The Record: Conducting Strong Interviews with the Media

Lagniappe Extracts

Before the beginning of Herman Melville’s epic novel, Moby-Dick, he includes what he calls “Extracts” as quotes from other sources about the “Whale” supplied by a “sub-sub-librarian.” The “Sub-Sub appears to have gone through the long Vaticans and street-stalls of the earth, picking up whatever random allusions to whales he could anyways find in any book whatsoever, sacred or profane.” And so, we attempt to extract from history the word of the month.

LAGNIAPPE

Most Americans have discovered the word Lagniappe through Mark Twain’s Life on the Mississippi, written in 1899, and still a favorite of English teachers who wish to project a picture of life at the turn of the Century.

“We picked up one excellent word—a word worth travelling to New Orleans to get; a nice limber, expressive handy word—“Lagniappe.”

They pronounce it lanny-yap.

It is Spanish—so they said. We discovered it at the head of a column of odds and ends in the Picayune the first day; heard twenty people use it the second; inquired what it meant the third; adopted it and got facility in swinging it on the fourth. It has a restricted meaning, but I think the people spread it out a little when they choose. It is the equivalent of the thirteenth roll in a “baker’s dozen.” It is something thrown in, gratis, for good measure.

The custom originated in the Spanish quarter of the city. When a child or servant buys something in a shop—or even the mayor or the governor, for aught I know—he finishes the operation by saying: “Give me something for lagniappe.” The shopman always responds; gives the child a bit of liquorice-root, gives the servant a cheap cigar or a spool of thread, gives the governor—I don’t know what he gives the governor; support, likely.

When you are invited to drink,--and this does occur now and then in New Orleans,--and you say, “What again?—no, I’m had enough;” the other party says, “But just this one time more—this is for lagniappe.” When the beau perceives that he is stacking his compliments a trifle too high, and see by the young lady’s countenance that the edifice would have been better with the top compliment left off, he puts his “I beg pardon, no harm intended,” into the briefer form of “Oh, that’s for lagniappe.” If the waiter in the restaurant stumbles and spills a gill of coffee down the back of your neck, he says, “For lagniappe, sah,” and gets you another cup without extra charge.”

But, it was written about liberally in magazines and essay collections before Twain’s book:

"Take that for a lagniappe" ( pronounced lanyap ), says a storekeeper as he folds a pretty calendar into the bundle of stationery you have purchased.

From: Dixie; Or, Southern Scenes and Sketches, Julian Ralph, 1896

And even in the American Journal of Pharmacy in 1890, as an explanation to pharmacists across America of the peculiar customs of New Orleans pharmacists:

“It is the odd customs peculiar to this place that make it so charming a stopping-place to the Northern tourist, it seeming to such a foreign country. Its large, airy houses, its lovely rose gardens, its peculiar and far-famed institution, the Carnival, are too well known for description here (besides not entering into the subject of this paper); but the odd customs extend also into the province of pharmacy, and of them the most peculiar is the institution known as Lagniappe (pronounced Lan-yap).

Lagniappe is something given to the purchase in a retail store, a bribe to secure his future patronage.

It is a custom extending back to time immemorial, its origin being account for by the following legend, which is given for what it is worth: Years ago, in the old Frend Quarter, there lived an old lady who had as a pet, a monkey, glorying in the high-sounding name, Lagniappe. The monkey was a well-known character in the neighborhood, and had a decided taste for sweet things; so, when the old lady went to market or to the grocery or drug-store she would always ask for an orange, cake or candy, “for Lagniappe.” Then the children in the neighborhood took it up, although, it is feared, the monkey obtained but a small portion of the good things given “in his name,” for, after he had been gathered to his fathers, and even to this day, we are asked to give gum and candy “for Lagniappe.”

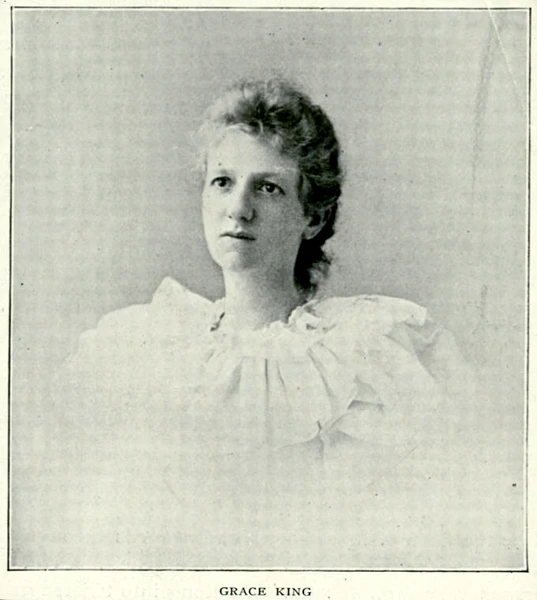

In 1891, Grace King wrote about Lagniappe for the Woman’s Council Table in The Chautauquan:

“TAKE it for lagniappe.

"For lagniappe."

"Here's your lagniappe!"

"Where's my lagniappe?"

"Don't forget my lagniappe!" - and so on.

One hears it in all the markets and market shops round about New Orleans, in all the languages and from all the racial varieties which the old creole city employs to carry on its retail affairs. They all are a unit on the subject of lagniappe, all want to receive it, and apparently all are equally eager to give it. Lagniappe is a symbol of the entente cordiale between seller and buyer, it is the souvenir of friendship between those friends who wish to make an equable and at the same time a profitable exchange of commodity and money; it is a sentimental effusion over one of the most practical details of life.

It is, to be technical, the bonus, the "extra," the voluntary gratification on the part of the vender after the bargain is concluded and over. It is understood to be perfectly voluntary. No court in the land could force one to give lagniappe. No human ingenuity could logically find a basis upon which to exact one. In no way can it be looked upon as a quid pro quo. Such a suggestion would show a most complete misunderstanding of the nature of the testimonial; for it is not lagniappe unless the bargain be concluded, and the business relations of seller and buyer terminated.

A strict application of political economical reasoning might prove that lagniappe was paid for, just as much as the previous bargains-over and over again by the consumer. In dollars and cents, perhaps so but the good will, the good humor, the interchange of compliment, would that be thrown in just so, after a dry business like buying and selling? If there were no lagniappe, how could a disagreeable wrangling be turned into a laugh, a vociferous squabble soothed into amenity? There is so much in life that we cannot buy, so much that we cannot pay for!

Read the rest here.

It is supposed never to be asked for, but that as we see is only a supposition. On the contrary, to go away from a counter or stall without your lagniappe, to pretend to be indifferent to it, to make it a matter of no consequence, shows an assumption of superiority, a make believe of riches, a "set-up-ness" for. When we ask a question of a fellow, which is only less odious to the genuine New Orleans nature, than a refusal to offer lagniappe.

The media, the currency of lagniappe, embrace every variety of commodity, but some seem especially adaptable to it, so much so, that one can live a lifetime in New Orleans and never know what it is to pay-for parsley, for instance. Who ever heard of buying parsley, or the onion, or tomatoes, or handful of loose vegetables for the souppot, or a bell pepper for salad, or red pepper for seasoning, or bay leaves for the gumbo? Some markets have better reputations for these generosities than others. In the old French markets "la Halle," as the Creole cooks call it, the abundance of lagniappe offsets the expense of a car fare to get to it.

The butchers give their lagniappes in remnants of meat and bone joints, to help the soup (and this is how a good soup can be had in New Orleans for "one" five cents, as the cooks say), and frequently the servants enjoy an extra "stew" from the same source. The bakers have a particular baking of little biscuits for the purpose; the candy sellers -ask a New Orleans street child what those jars of pink and white peppermint cubes on the counter are, for such a child would ignore that that particular kind of candy was ever sold anywhere. The small grocers give ginger, nuts, raisins, or pecans; the dry goods people an additional quarter, sixth, eighth of a yard. "See what good lagniappe I am giving you," they say while they are measuring it off. The laundress, cook, waitress, scrubber, have also their way of “throwing in" lagniappes.

One who is accustomed to the quaint French-Spanish-African custom finds a disappointing stinginess of word and deed in a lagniappeless country, where there is simply the punctilious conscientious performance of the compelled one mile, and no proffer of the "twain." Where the volubility of grateful thanks is met by the "not at all," and the service rendered is nullified into a "nothing." A service so depreciated, humiliates, rather than relieves, the recipient, and the waiving of thanks is dismissing the thanks. Is it not good for us to be under obligations one to another, to give lagniappes and receive them? Can a pleasant human intercourse be based upon the "small profit, quick returns, and cash system" of the sharp trader? Have we not each of us a little lagniappe of our own to give away, some little part of our own individual commodity? Can we not with benefit to our hearts and to our language adopt in the one the custom, and in the other the word, and so amend both?”

And Campbell MacLeod details the attempt of the Crescent City to do away with the practice in April 1910 for Sunset, The Magazine of the Pacific and of All the Far West, here abbreviated:

“THE city of New Orleans was recently in a state of ferment the edict that went forth that after that date no more lagniappe would be allowed to be given away. The curious feature of the fight is that grocers and those merchants who gave it are fighting quite as much as the recipients of the gifts. And the bewildered stranger seeing the aggressive signs posted everywhere has asked "What is lagniappe?"

Lagniappe is the quaint Creole custom of giving good measure. The volatile downtown clerk in that section of the city which someone has happily called "Lagniappe Town," loves to explain to curious visitors that it is simply a token of his and his employer's frien'ship for you to make you remember the store where a friend, even if he is a stranger, is recognized at sight and decorated with a souvenir of his affinity's affection.

It's monstrous to think there will be no more lagniappe given in New Orleans.

The Crescent City without lagniappe will be the Carnival without the king.

The taking away of it will assume the tragedy of removing an ancient landmark. Without lagniappe where will come in the fun of the small boy's running errands for his mother? For say what they will this pretty custom was an incentive to obedience. When small Emile was sent to the corner drugstore for cough medicine for the baby to know that he would be given a lemondrop or a piece of a piece of peppermint-gum repaid him for his trouble. But they are saying, those in authority, that the enforcement of this law will be the salvation of the small person's digestive organs. That pink pipes and chocolate cigars inexpensive enough to be given away recklessly must naturally be too cheap to be put into the precious little human stomach.

But what are you going to do about it? asks the corner groceryman.

Read the rest here.

...

Lagniappe has been a sort of rosy lining to the dark side of life dispensing lagniappe these forty odd years when the kid is on one side of the counter Jean Antoine's youngest-who cannot read the staring big sign over the clock:

NO MORE LAGNIAPPE

Crying great wet tears of woe for lagniappe to go with the five cents worth of ground coffee he came to get for his mother. You can't explain to one of his age and temperament that They say Lagniappe has got to go.

Knowing ones declare that once upon a time a certain woman-miser moved to New Orleans and squandered her savings out of sheer curiosity to find out what she would get for lagniappe. And who can resist it? A gift in the bosom does pacify even the most practical of us amazingly. Something for nothing is a seductive melody. At the old French Market any morning in the week, preferably Sunday, you would have seen them-the local lagniappe grafters in all their glory. Old and young, big and little, black and white, and all shades of yellow, from café-au-lait to chocolatebrown, with a good sprinkling of Choctaw Indians to give the needed red note in the color scheme-they come, each armed with a basket, taking their leisurely way, on all sides demanding the lagniappe that is theirs by right of time-honored observance.

Even one another. And when that most august, if oft-repeated, state occasion rolled around when "mon cher cousin" is coming to dine, everybody was called upon to contribute to the feast. There was always a fringe of children around the various stalls where the stately river steamers wait for cargo at the New Orleans docks by her social gifts and graces on her regular morning rounds, and the rice she wheedled the corner groceryman out of yesterday morning will go to make a gumbo that will fortify her for a similar pilgrimage tomorrow morning.

Such a thing as spending real money for parsley, mint, onions or garlic, dear to the downtown epicure, was an unheard-of extravagance. These were the favorite lagniappe donations from the vender of vegetables to his customers. The Creole baby was born with pink sugar on its tongue, and from the infants on up, they could wheedle anybody out of anything,-from crying infants on up to ten-year-old boys and girls who were "too sick to go to school to-day”— but were able to drag down here with an indulgently gentle scolding mother to bring the basket and beg a joint of a stalk of sugarcane or maybe an orange that was beginning to soften past the possibility of sale. Hurt them! -the lagniappe not much!-lagniappe is good for children- even sick ones.

Are Lagniappe is as highly pleased as the cipient of his bounty. He calculated it all out a hundred years ago when his grand mere kept this same stall-that when one gives three carrots for a nickel its good business to throw in a banana and two half-spoiled bunches of grapes for lagniappe. It's satisfying all round-the feeling that one has got something for nothing.

The feminine drivers of the milk carts that are one of the picturesque sights of New Orleans also know human nature, and drive bargains quite as skillfully as they do the angular animals hitched to their queer vehicles. Even the small son of Madame the Milkwoman has eyes to see-see quite as much as do those of his mother perched aloft in state. One sharp-eyed Jehu under a black slat sunbonnet hides many a crafty smile from her customers. "Yais, yais!" she will murmur from her lofty pinnacle behind the shining milk cans to Madame of the House who carries on the conversation behind a lace-curtained window, giving on an upper balcony.

...

Lagniappe is a very pretty sociable custom-and the givers of lagniappe have had their inning at Christmas and Easter and all the ten dozens of holidays that the true Creole religiously observes. They are given to throwing out hints, these givers of lagniappe as the various seasons approach that they stand with outstretched arms ready and willing to receive whatever it may please their customers to put into them. Indeed small persuasion leads them to drop hints as to exactly what gift would be most appreciated.

What would life be without lagniappe? We are all ridiculously alike when it comes down to the ground floor of human nature. And in one way or another we all waste our substance for lagniappe. Perhaps not quite so flagrantly apparent as the barter that goes on in downtown New Orleans, but quite as indisputably.

A certain widow who prides herself on the way she manages her small insurance income, lives in an apartment house where she pays thirty dollars for a room, dark, damp, and on the third floor. She keeps this room year in and year out because there is an electric bell in it, and the landlady sends up a pitcher of ice-water several times a day. True, the bell rings only semi-occasionally, but the ice-water is carried to her room whether she rings for it or not. This woman stays there though the place is in no way inviting-she admits that she is ashamed to ask any of her friends to come to see her, but she is unable to resist the ice-water. She is willing to put up with the bad ventilation and poor service for what she calls "the extras."

Lagniappe! What good money we waste paying for it. But maybe it isn't wasted, for we get the value of it in the satisfaction of feeling that we've been given something free-gratis. We love it no matter what circle we move in the smart set or catalogued with the cook's friends. Life would be a dull business if we didn't.

…

Lagniappe-what is it? The vari-colored bubble that compensates for the wasting of a good cake of soap; the jingling pennies that reconcile us to squandering a gold piece to get "change"-the alluring current in life's cake, irresistible and indigestible. The pink frosting that conceals the hole in the masquerading doughnut; a freewill offering that has as many strings attached to it as a gift library; the tinsel toy that makes a multimillionairess with tears in her eyes implore a masker on a Mardi Gras float to throw her the foolish mysterious trinket instead of to the ladies on the next balcony.

Lagniappe! It's as elusive when it comes to defining as the charm of New Orleans herself something for nothing and because you are you, a gift in the bosom-lagniappe!”