News

Marketer Magazine: On The Record: Conducting Strong Interviews with the Media

The King that Never Was

“There never was and there never will be a king like me.”

It was the title of a play that just struck John L. Metoyer. Probably because he saw himself in the fictional African King Zulu, having a laugh at his own expense. We can picture Metoyer as a laborer in the late 1800s and early 1900s. He could have been a longshoreman or a dockworker. He was working by day and night, first as a laborer and then as a member of The Tramps in a deeply segregated New Orleans. The Tramps were a mutual aid society and social club that provided things like medical or burial costs and financial assistance for family emergencies for Black community members. These types of aid programs were critical during the Jim Crow era for services, of course, but they also served as sanctuaries of self expression, pleasure and communal cultural displays.

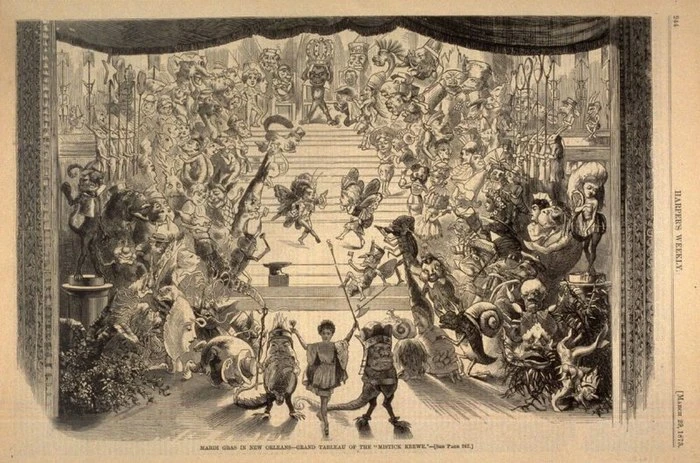

Surrounding Metoyer and his friends were the sights and smells of a lavish, elitist existence that simply didn’t belong to them; that mocked them with performance pageantry and the celebration of power and social hierarchy that wasn’t lost at sea on the voyage to the New World. Carnival krewes existed as early as the 1850s as a nod to European traditions and customs. The first krewe to display their social standing in lavish costume and with displays of wealth tossed into an admiring crowd was called the Mystick Krewe of Comus—they were parading in a similar fashion until a 1991 municipal law that stated Mardi Gras krewes in New Orleans couldn’t discriminate against race, gender, religion or sexual orientation seemingly prompted the end of their public facing persona. Some say Comus now operates as a private, invite-only social club under a different name. Or that deeply intertwined history is the assumption, anyway. Comus’ successor from the early 1870s, Rex, is a krewe with a similar history, refined aesthetic and level of pageantry that still rides yearly during the Mardi Gras season.

It was the onslaught of these displays from Comus and Rex, coupled with the play he saw about that African King Zulu that never was, that gave Metoyer an idea. He and his friends down at the mutual aid could parade in their own subversive and joyfully defiant way. They could paint their faces, make costumes from scratch and do their absolute best to mock the mockery. They could throw out a lagniappe of their own. It couldn’t be glass beads or collectible coins, no, but it could be something they had access to, at no cost to them. Coconuts.

Metoyer and his friends named their krewe Zulu, and as such, Metoyer became King Zulu…quite poetically, the king that never was and never will be. Through theatrics and angst channeled into art, this group of laborers claimed their visibility. And it persists to this day. To receive a lagniappe from the Zulu krewe likely means a coconut on display in your home for well, longer than one might display any other tree fruit. Because whether the detailed history of this particular little something extra is known or not, there’s something about a gesture so humble that translates as simply grand.