News

Marketer Magazine: On The Record: Conducting Strong Interviews with the Media

The Hamburger that Ate the World: How Bias Birthed Rock ‘n Roll

Outside of religion, royalty and war, it’s a safe bet that rock is the most written-about subject since the dawn of the printed word.

And much like religion, royalty and war, few things have had a greater impact on the way the world turns.

The roots of rock are a tangled bed of influences, including R&B, country, gospel, jazz, classical and swing. But its origins are as controversial as the music; born out of envy, discrimination and greed.

At the end of World War II the greatest generation, who had known only depression and war, was finally able to chase the American dream on their own terms. With a booming economy and a baby boom underway, life was good, conventional. Suburbs flourished. And families revelled in steady jobs, modern-day perks and new-fangled appliances.

In the early 50s, television was gaining popularity, but radio was still king, ruled by wholesome artists singing wholesome tunes.

Then in 1952, the song writing duo of Jerome Leiber and Michael Stoller ventured to a Black nightclub to hear popular R&B artist Big Mama Thornton. They later said of that evening, “She was raw, nasty. We loved her.” Inspired by her sensuous sound, they ran home to compose. Ten minutes later, they’d finished Hound Dog. And although it reached number one on the R&B charts, it went unnoticed in suburbia. For what it’s worth, Big Mama Thorton was also the catalyst for a young choir soprano to want to sing with “soul.” Janis Joplin started as a teenager trying to sing like Big Mama, eventually recording her song Ball and Chain, among others.

One group that did take notice were mainstream radio stations. They loved the raucous R&B sound, as well as the catchy tunes and smooth harmonies of Black groups like the Cadillacs, Chantels, Coasters and Drifters. But even with the innocence of doo-wop, they knew this “race music” would never be accepted in their top 40 playlist. And for the time, were resigned to wonder how they could get in (and cash in) on the act.

Oddly enough, the answer came from a country swing band from Pennsylvania, who had a regional following with their up-tempo, danceable tunes. In 1954, Bill Haley and His Comets recorded Rock Around the Clock. At first, sales were sluggish. But a year later, after it was added to the soundtrack of the gritty urban film “The Blackboard Jungle,” sales skyrocketed and it became the biggest hit of the year.

One resourceful disc jockey in Cleveland named Alan Freed realized that this “Black rhythm by a white artist” could be the anthem for a growing generation of rebellious youth — and what “in” radio stations had been waiting for. In fact, Freed is credited with coining the phrase “rock and roll” (which was already a common inner city reference to sexual relations).

Slowly, the tamer Black artists began getting airplay on predominately white-oriented stations, as well as being added to the roster of traveling rock revues.

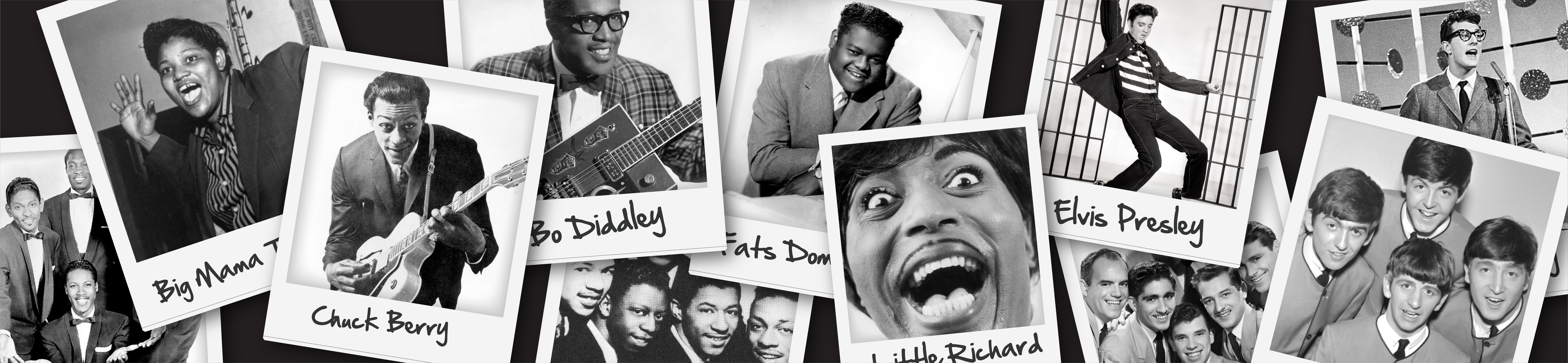

Despite this meager progress, these groups found attention from major record labels and crossover radio acceptance was a difficult ceiling to break. Even as new sensations such as Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Bo Diddley, Big Joe Turner and Fats Domino were gaining steam and beginning to chart, mainstream success still proved elusive. But when Fats Domino made the top 10 with Ain’t That a Shame, record producers saw the one true path to take this movement a step further. And that was to have a white artist put a bland spin on a black tune. That way, parents would be pacified and segregationists would be satisfied. Their first venture into this experience was to allow Pat Boone, arguably the whitest guy in America, to re-record Fats Domino’s hit, taking it to number one. As evidence of his squareness, Boone lobbied to change the title to Isn’t That a Shame, so as not to upset his core audience. Which, had he gotten his way, would have really been one.

This bait and switch worked beautifully, but those in charge knew there was still something missing.

For that discovery, fate found its way to Memphis, where Sam Phillips, a sound engineer and founder of Sun Records, met a teenaged truck driver named Elvis. A constant and annoying presence at Phillips’ studio, the kid begged for an opportunity to record, even offering $3.95 with the promise he had a sound like no one else. And with his rendition of That’s Alright, Mama, he delivered on that promise.

It was an ironic twist only rock and roll could produce. From white artists merely covering soulful Black tunes, emerged a soulful white artist covering Black tunes — that audiences believed to be Black!

Radio stations saw their moment and seized it, playing Elvis’ tunes nonstop. Parents were aghast. Burgeoning baby boomers were riveted. Teen girls swooned. And within six months, Elvis had gained more notoriety than any other artist in history.

Record execs didn’t get this new music. They also didn’t care. All they saw was a growing demand for it and began scouring the country, signing Black artists they knew would further open the floodgates Elvis had tapped.

At long last, true rock and roll pioneers such as Chuck Berry and Little Richard, were given the opportunity to nab big recording contracts, perform their own tunes and receive mainstream acceptance from a multi-racial audience. Little Richard’s gender-bending looks and maniacal screams worked America’s youth into a frenzy. And Chuck Berry's songwriting talents and trailblazing guitar licks earned him the title, The Father of Rock ‘n Roll.

Even white groups such as Buddy Holly and the Crickets and The Everly Brothers were finding equal footing among these giants, bringing guitars into the forefront and setting the stage of what rock — and the rock and roll band — was to become.

More than the records, kids clamored for live performances. But the mania brought on by even the tamest of rockers resulted in crushing crowds, concert riots and renewed consternation from concerned civic leaders.

They found rock and roll trashy and too “culturally diverse” for their liking. They saw it as the devil’s music and were convinced that continued exposure would lead to juvenile delinquency, irresponsibility and ultimately sex and drugs (they were right, of course). But with every move to censor it, teens countered with blind devotion and record-setting record sales.

Pressured by parents who saw their idyllic lifestyle in jeopardy, civic leaders turned to the government. Unable to stop something that was perfectly legal, the government decided to create the illusion of impropriety, and thus, illegality. Massive investigations into what became known as the “payola scandals” (the practice of radio stations and DJs taking bribes to play certain songs from large record companies) captured America’s attention. And though this practice was also perfectly legal, the negative publicity slowed the rock landslide — but in the process ruined many careers. Within five years of the scandals, Alan Freed had died, disgraced and penniless.

Now don’t get us wrong, rock was still rocking. But a series of unfortunate and scandalous events beginning in 1957 gave adults added justification for their cause.

Elvis was drafted, saving millions of young girls from the “threat” of his swiveling pelvis. Little Richard left music for the ministry. Jerry Lee Lewis married his 13-year old cousin. And Chuck Berry served time for transporting a teen girl over state lines.

Fans were stunned. Parents were thrilled. And record labels quickly shifted gears to control the damage and keep profits up.

Their answer to taming the rock monsters (without losing the rock fans) was to take a giant step backwards, offering clean-cut (and we assume government-approved) stars such as Paul Anka, Fabian and Frankie Avalon. Sure, the rock was there, but the edge was gone. And for the moment, it seemed this parental victory would keep their world intact.

But across the pond and far from their prying eyes, a transformation was taking place that would change everything. Teens throughout Europe and especially in England had been following America’s new, exciting beat with equal fervor. And had shared equal frustration at the setbacks it incurred.

While both were introduced to rock via radio, kids in the U.S. had easy access to 45s and LPs whereas kids in the UK did not. And they knew what stations were spoon-feeding them was neither the soulful R&B nor the kickass rock they had gotten a taste of – and hunger for.

In what has proved to be the greatest timing in the history of music, entrepreneurial merchant seamen began buying up American albums to sell to their fellow Englishmen. Among the lucky recipients were two lads from Liverpool named John Lennon and Paul McCartney.

Listening to artists like Chuck Berry, Larry Williams, Elvis and Barrett Strong didn’t just excite them. It rewired their DNA. This music became their life and religion. Initially, they imitated. Then improvised. And finally, improved. While it would become yet another instance of whites covering (and outselling) blacks, what the Beatles took and gave back to America was earth-shattering. World-changing. And for that, we can forgive them.

Tunes that turned the tide:

For those who weren’t there (which is most of us), but are curious as to which songs broke through racial and creative barriers, here are a few ditties from the mid-50s to early 60s that exemplify what the fuss was all about:

- Rock Around the Clock: Bill Haley & the Comets

- Ain’t That a Shame: Fats Domino

- Hound Dog: Big Mama Thornton and Elvis Presley

- Long Tall Sally: Little Richard

- Bye, Bye Love: The Everly Brothers

- Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On: Jerry Lee Lewis

- Peggy Sue: Buddy Holly

- Green Onions: Booker T & the MGs

- Sleep Walk: Santo & Johnny

- You Don’t Own Me: Leslie Gore

- Heat Wave: Martha & the Vandellas